Lessons Learned and Not - Heists of the 1930s

A constant “student” of crime, Jack Kelley analyzed other crimes not to replicate them, but rather not to repeat their mistakes. We are taking one last journey to the 1930s to examine some of the lessons Jack took away from his own experiences and those of his contemporaries, some of whom would later be arrested for the 1950 Brink's heist.

For a transcript of this episode visit our website. Follow us on Twitter for sneak peeks of upcoming episodes. You can also find us on Instagram and Facebook.

Questions or comments, email lara@doubledealpodcast.com or nina@doubledealpodcast.com

Thank you for listening!

All the best,

Lara & Nina

Lara:

Hi All! Today we are going to be discussing some of the robberies and the men believed to have committed them in and around the Boston area in the 1930s. A few of the men we’re discussing today would later be convicted of the Brink’s Heist of 1950. Jack “Red” Kelley, my father’s mentor, ran with a few of these men, so we thought it would be interesting to have one last look at what Jack might have been up to prior to the thefts we covered in our first episode, and what he learned from their errors. A constant “student” of crime, Jack studied other crimes not to replicate them, but rather not to repeat their mistakes.

Nina:

Well, if Jack hadn’t been smart enough to separate himself from the men and women we’re talking about today, we might not be doing this podcast!

Lara:

True! But I suspect dad would’ve still managed to tangle himself up with other interesting characters to give us more than enough to talk about.

So Nina, who or what are we covering first?

Nina:

I think we should talk a bit more about Jack and his family.

If you’ve been with us since the beginning, you’ll remember that Jack was born in Watertown in June 1914. He had two older sisters, and an older brother named James. Like Jack, James was extremely intelligent. After graduating from St Patrick’s High School in Watertown, he attended the Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology. James went to work for the Boston investment firm J M Forbes in 1929. He spent his entire 44 year career at Forbes, working his way up from a stenographer to an accountant.

Lara:

Well, I guess you could say that Jack and his brother, James were both in banking. James dealing with the deposits and Jack the withdrawals so to speak.

Nina:

Yeah, you could say that. I of course have my suspicions that maybe some of the tips Jack got may have come from his brother. Not necessarily intentionally, but he did have an inside track. Speaking of banks, why don’t you start with the first robbery we’re covering today?

Lara:

The first heist we’re going to look at is the Brookline Trust Company on October 2, 1933. The getaway car drove up to the front of the bank, five men exited the vehicle, leaving the driver behind the wheel. Two men stationed themselves at the entrance of the bank, while the remaining three entered. They ordered 10 customers and the bank employees to line up against the wall and held them there at gunpoint. One of the robbers ordered a teller to open the door to the rear of the bank. Once inside he swept piles of bills totalling $20,000 into a black bag.

In the meantime, a female clerk was able to sound the alarm for the police. A lone policeman arrived but he was quickly disarmed and forced against the wall with the other hostages.

Nina:

Another man who was parked out in front of the bank leaned on his horn to alert the police himself, but he was stopped by one of the men waiting outside.

His compatriots quickly exited the building, got in the waiting car, and raced off towards Boston. The getaway car was reported abandoned in Roslindale the following evening. It had been rented from a company in Cambridge by a man using a fake id. He reportedly said that he was going to a funeral up-state. The odometer showed that 73 miles had been put on the car since it had been rented. The vehicle was dusted for fingerprints but nothing useful was found.

Lara:

The assistant treasurer took a heart attack while on vacation in Maine less than two weeks later. He was only 50.

Nina:

All roads lead to Maine!

Lara:

I know! So Nina, what similarities did you find between this holdup and some of Jack’s?

Nina:

The professionalism struck me at first. That and no violence used.

Lara:

Two of Jack’s trademarks.

Nina:

One thing that was different was their use of a rental car.

As you’ll see, though, what really stood out to me was the pattern. Like in Jack’s later jobs, this crew seemed to do three jobs close together and then take a break. Which leads us to the next robbery a little over a month later.

Lara:

On November 11, 1933, the First National Bank of North Easton was robbed by three men just as the lone employee was returning from his lunch break. They appeared at the door suddenly. One of the men waited in the lobby to keep an eye on the entrance. The other two held up the clerk with a blue steel revolver and a nickel plated weapon. The shorter man, at 5’7” and weighing 160, vaulted over the counter, scrambled over the grill and ordered the clerk to open the vault. Covered by the two weapons, the clerk obeyed. The second robber was described as 6 feet and wearing a dark suit. The amount stolen was estimated to be between $10 and $12 grand, mostly in 20s and 10s. No clues were left behind. The clerk was then ordered into a small back room and told to stay there for five minutes. He was not locked in or tied up, so he was able to contact the telephone operator right away instead of the prescribed 5 minutes.

Nina:

The only clue the cops had to go on was that of a local gas station employee who observed a faded blue sedan parked nearby at 11:50. When he returned from his own lunch at 1:30, the car was gone.

This is where I start to get suspicious about inside information being passed. How would the thieves have known that the clerk was alone that particular day? It was not a normal practice. The other employee was out that day at a meeting in Boston. It was the day after payday and the local factory that used the bank had paid their employees by check. That meant that the factory employees would come to the bank to cash those checks after they got off work on Saturday afternoon. So, in theory, the bank would have extra cash on hand for that purpose. But maybe they didn’t. It was the height of the Great Depression after all.

Lara:

Obviously, most of the robberies we are covering this season, at least the ones pertaining to Jack, were successful due to inside information or having someone on the job. We know for certain in the case of the 1968 Brink’s robbery that it was one of the guards. There is of course the possibility that there may have been a single person feeding information on multiple robberies, but let’s not openly speculate on who that was.

Nina:

What’s our next job?

Lara:

On December 4, the Quincy Trust Company in Wollaston, the same one Billie Aggie would rob some 20 plus years later, was held up by five men a little before the bank closed at 3 in the afternoon. A local attorney walked in on the holdup and was hit in the back of the head with the butt of a pistol twice when he hesitated to drop to the floor as ordered by the thieves. All of the money was scooped out of the cash drawer in the commercial department totalling about $20,000. 7 $2 bills were left behind, leading the authorities to believe that the thieves were superstitious. $5000 in checks were also left undisturbed.

The vehicle was later found abandoned in the Hyde Park section of Boston. The license plates had been reported stolen in Cambridge the month prior.

Nina:

The stolen vehicle with the stolen plates are definitely reminiscent of Jack’s later jobs. And the superstitious bit with the two dollar bills.

Lara:

Remember the case from the Shawmut Bank robbery? That Roslindale guy was convicted because a handful of $2 bills were found in his wallet. No witnesses to ID him. Nothing, but he still went away. The fear of $2 bills was justified. As for the plates and the vehicles, we know that in every one of Jack’s robberies, the cars and plates were stolen.

Nina:

More than just superstitious when it comes to the $2 bills.

The authorities believed that they’d finally put an end to the bank hold ups with the capture of the Millen Faber gang in late February 1934.

The gang had gone on a two month crime spree that resulted in the murder of two cops. Two more men were shot but survived. After robbing a bank in Needham of more than $14,000, the trio also kidnapped the treasurer of the bank. The kidnap victim was freed after being forced to cling to the running board of a stolen black sedan during their getaway.

Lara:

A much younger Joseph Dinneen was there to save the day. You might remember Dineen from our episode about the Brink’s heist in 1950. Magically, he had written about that case almost exactly as the trial testimony of Specs O’Keefe would read two years later. Joining him in solving the Millen Faber Gang case was another journalist named Lawrence Goldberg. The two men later received $2000 each from the governor as a reward for their services. The man who had turned the Millens into the police got nothing.

Nina:

But the authorities were wrong in their assessment. Not a month later, the $26,000 payroll of the Diamond Shoe Company was robbed at 9:45 in the morning by five men in a sedan. Two of them were armed with submachine guns, two with shotguns, and one with a revolver. The payroll was in one large canvas bag weighing about 50 pounds. The money was being transported in a car that had “Home National Bank” painted on the back doors.

Lara:

Now that sounds like a Jack robbery!

Nina:

No question. The robbers arrived about 30 minutes before the bank car passed by. Two men got out and waited at the street corner. Two men stayed in the sedan with the driver who would drive 50 yards in one direction, turn around, and drive 50 yards in the other direction. Instead of making anyone suspicious, it appeared to the casual observer that a driving lesson was taking place. He almost hit a pedestrian at one point, but didn’t respond to the young man yelling at him.

Lara:

The bank car was now 20 minutes behind schedule. As it finally turned the corner and came into view, the driver of the robbers’ car backed up and forced the bank car over to the curb in front of the office of the Lawson Coal Company. The two robbers who were standing at the corner, walked up to the bank car and took positions on either side of it. The other two men hopped out of the car. The driver remained in his position, holding a machine gun in front of him.

The bank messenger was armed, but was quickly forced to drop his gun when threatened by one of the robbers, who grabbed it. Another robber reached inside the bank car and grabbed the canvas bag.

Nina:

Another car rounded the corner but he couldn’t have been moving that fast because another robber grabbed the keys out of his ignition and told him to be quiet. Meanwhile, the front tires of the bank car were slashed by one of the men with a shoemaker’s tool. The robbers “overlooked” another payroll bag in the back of the car. This one was intended for the Douglass Shoe Company, but only contained $733.

The thieves fled the scene in the same car they’d arrived in, but not before a witness got the number on the license plates. The plates had been stolen on March 21, and did not belong to the car. The police were on the scene in less than three minutes but by then the robbers were long gone, headed back toward Boston. Planes were sent up to try to find them from the air, but they were unsuccessful. The money was, of course, untraceable. There had also been $586.91 in silver and copper in the bags.

Lara:

A sedan was found in the Atlantic Street section of North Quincy the following evening. It was unmarked, but a set of brand new 1934 Maine license plates were found in the backseat. They were traced to a man from Auburn named Israel Winer. Winer claimed that the car had been stolen in Boston more than a week prior. Fingerprints experts were unable to find anything useful, and it was later determined that the vehicle found in Quincy was not the car that had been used in the robbery.

A few days later Nicholas Gaeta, Ernest DeAngelis, Francis Healey, and Philip Massa were arrested in connection with the robbery as accessories before the fact. Gaeta and DeAngelis were freed on bail on April 9. The next Grand Jury was scheduled for June, but it appears that nothing ever came of the case.

Nina:

Months passed. Another pattern that matches Jack’s. Three jobs, then a break, then another job.

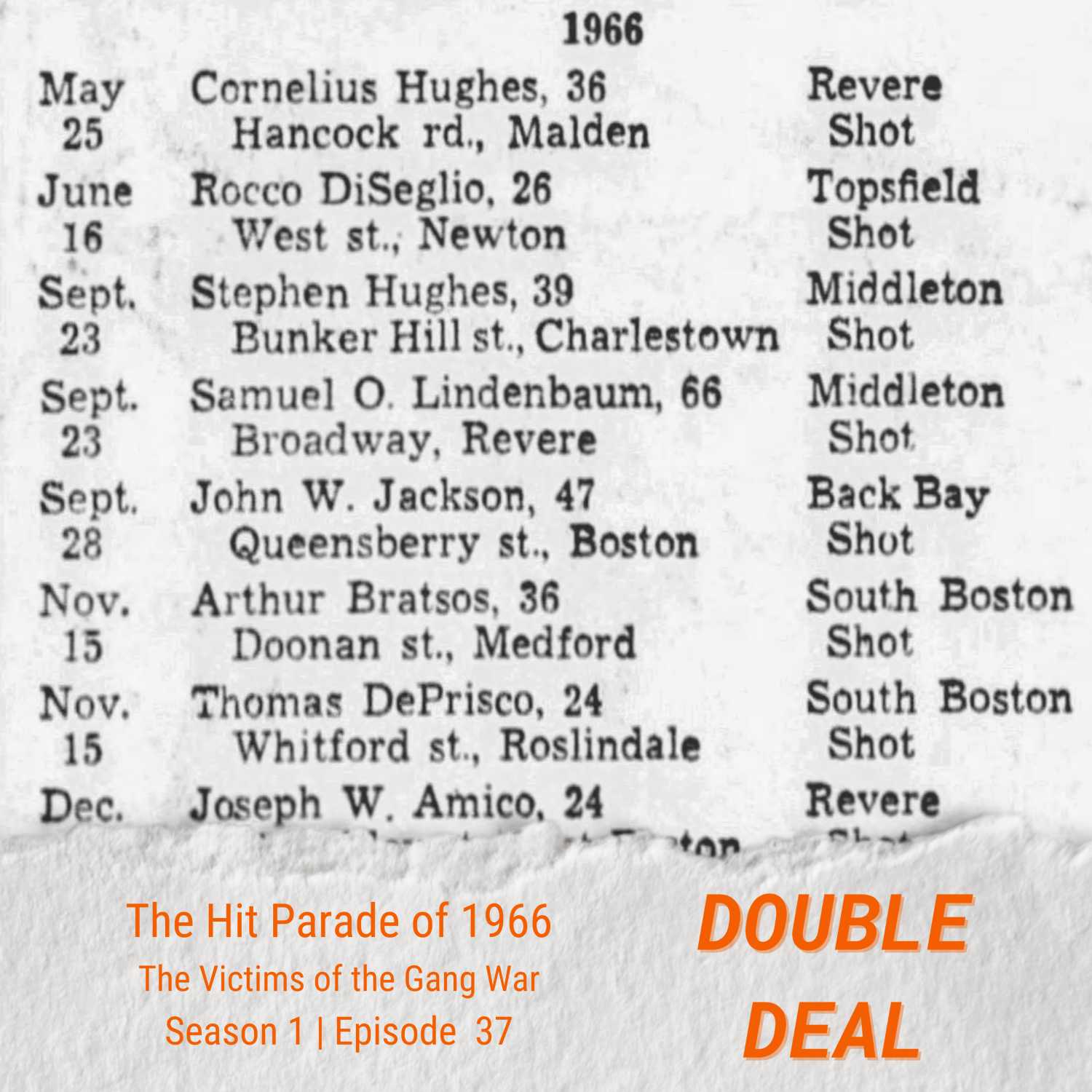

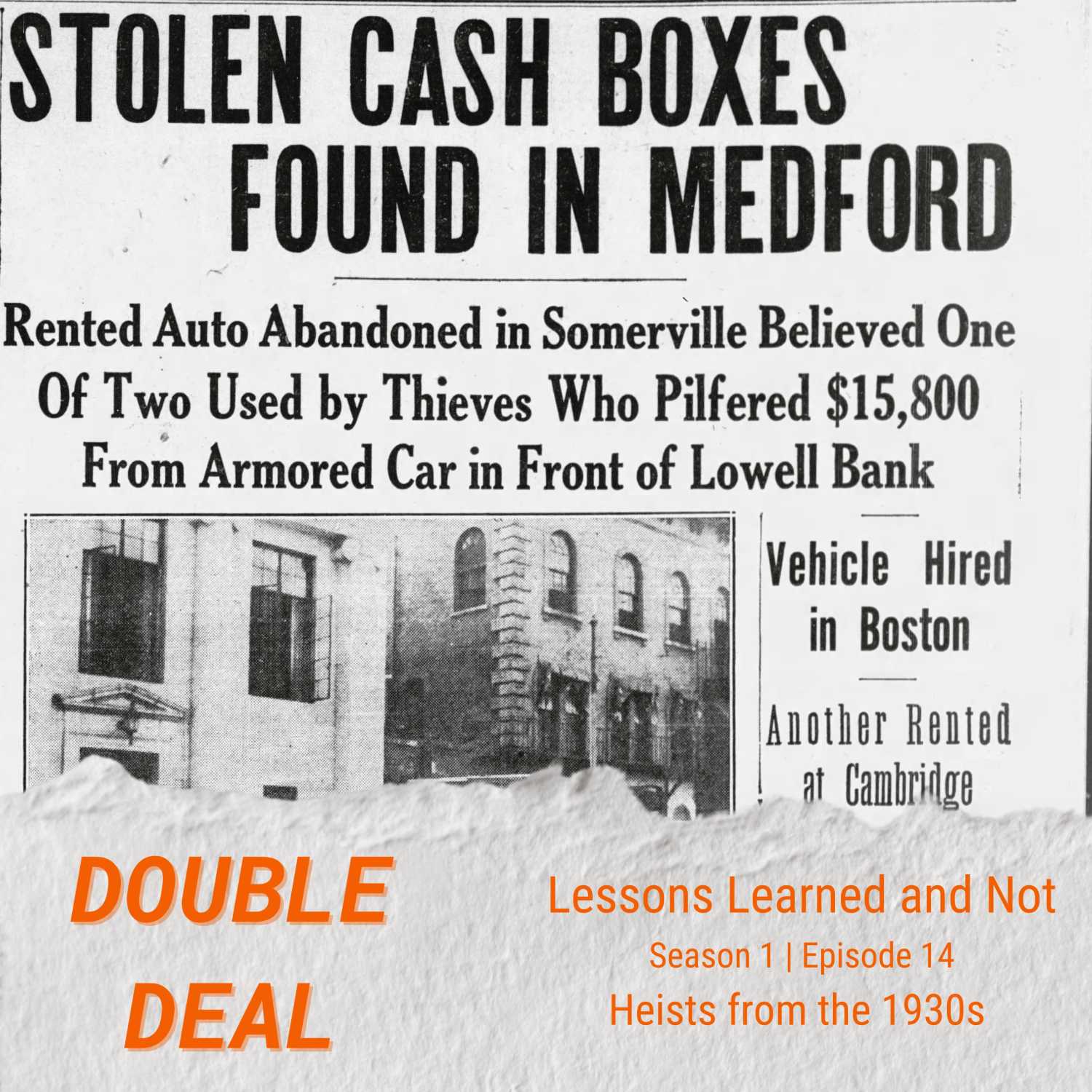

On Friday August 10, 1934 an armored car was robbed of two payrolls outside the Union Old Lowell National Bank on John Street. The theft took place shortly after 9am. It was conducted so smoothly that the bank guards in the car didn’t even know they were robbed until they made their next stop. They went to get the next payroll for delivery from the back of the car and realized that two payrolls were missing. One was a little over $14,000 that was set to be delivered to the Lawrence Manufacturing Company of Lowell. The second was a much smaller payroll of $1670 for the Royal Worsted Company. Thinking that maybe the bank had made a mistake, the guards returned there. But it wasn’t a mistake.

Lara:

Another one I would say Jack was involved in. I wish I knew who he was working with though!

Nina:

Me too! This one reminds me of two jobs that we’ve talked about in previous episodes. The Thompson Wire Works in Mattapan in 1947, where $20K was taken while the guards were delivering another payroll.

The other job it reminds me of is Danvers. The armored truck parked in front of a drugstore on Danvers Square after making a delivery, and the guards jumped out for their usual mid-morning break. While they were inside getting their coffee, three men broke into the truck. They transferred over $600,000 into a waiting Buick that was double parked, and sped off at 85 miles per hour.

Tell us what happened in the Lowell Armored Car robbery.

Lara:

A witness reported seeing two sedans pull up beside the armored car. A man dressed in a uniform similar to the one worn by the bank guards exited one car. He opened the back of the armored car, and removed two boxes of payrolls. He got back into the sedan, and the two cars sped off toward Lawrence.

As the police tried to reconstruct the crime, they concluded that the thieves must have had inside information in order to pull off the crime. Their theory was that the robber got inside the back of the car while both the guards were in the bank.

Nina:

Insurance required three guards only if the money carried was more than $25,000. Since the total was less than that, only two guards were assigned the route that day. This was the first time in months that this had been the case. One guard carried the boxes out of the bank while the other protected him. The guards had failed to lock the right side door when they left the car unattended.

Lara:

The compartment in the back was only 4 by 5 feet. The robber concealed himself by standing close to the door. He waited there until the guards slid the two boxes of payroll money onto the floor next to him. After they closed the door again, and were getting back in the front seat, he opened the door, hopped out, and took the box of money. He closed the back door at exactly the same moment the driver closed his door. Neither of the guards heard a thing.

The guards had the box for their next stop in the front seat with them, so they didn’t even notice that anything was missing until after they’d dropped off that payroll 20 minutes later. The empty cash boxes were found in Medford on Friday afternoon by some schoolboys. Forty cents had been left in one of them, and the boys were each given a dime as a reward.

Nina:

The two sedans were later discovered to both be rentals. One had been hired from the Mt Auburn garage in Cambridge. The other had been hired from an agency in the South End. In both cases the name and address given were false. A man had called the Cambridge garage on August 9, and said he’d be keeping the car overnight. The Boston rental car was found in Somerville late Friday night.

Lara:

But for the police theory to be true, that implied that the thieves had inside information about when the armored car would arrive for pickup, how long the guards would be in the bank, and that there’d be only two guards instead of the usual three.

Nina:

The fact that the payroll was less than $25 grand makes sense to me because it was August and people would have been on vacation. So that’s fewer pay packets that you’re sending. Anybody could have deduced that. But some of the other parts make me think again that it was an inside job. Maybe upper management didn’t have the funds to cover the payrolls. Or there was fraud going on.

Lara:

The following morning, a 23 year old named Carroll Smith was arrested at his home in Lowell. The lone witness to the crime reportedly identified Smith as the man he’d seen exiting the van. Smith was held on $20,000 bail, significantly less than the $75,000 the police chief had requested. The trial was expedited and by Thursday the charges were dismissed.

Nina:

Talk about rights to a speedy trial. Five days and it was all over. After that failure the investigation turned south to Rhode Island. In the meantime, the company insuring the payroll launched their own investigation. Nothing was mentioned for months.

Lara:

On November 30, 1934 the former VP of the bank in Lowell was found lying face down in his hotel room in New Hampshire. The smoking revolver he’d used to shoot himself in the head was nearby. Ivan Small was still alive, but died just a few hours later in the hospital.

The following day a small article appeared on the second page of the Boston Globe. The headline read: “Lowell Banker’s Accounts Short”. The article revealed that Federal examiners had been quietly investigating the bank in Lowell for some time. They’d already found $25,000 missing and expected to find more. The article alleged that the now dead VP was the culprit. Small had resigned from his position at the bank in February, citing poor health.

Nina:

Like I said, fraud. Not to get too conspiratorial, but it almost looks like upper management were hiring these out.

Lara:

I think you might be right about some of these heists being used to cover for embezzlement of one sort or another. What’s the next heist you want to cover?

Nina:

Those were the successful robberies, now we’re moving into the failures. We’ll start with Brockton City Hall. It was robbed of nearly $13,000 on the morning of October 16, 1934. Four or five men entered the building shortly after 9 am. Three of them were wearing what were described as “working clothes”. In addition to the cash that they swept up into a paper bag, the men escaped with the service revolver of the guard on duty, and a riot gun. The holdup was described as “carefully planned”. It was carried out so quietly and smoothly that nobody realised what was happening until it was too late to sound an alarm.

Lara:

The only clue available was that of a witness who noticed a maroon sedan waiting for them as they exited the side door of the building. The driver allegedly went speeding toward Boston, hitting another automobile in its haste to get away. When they reached the West Side of Brockton, they switched cars.

The maroon sedan was discovered at 10 o’clock that same evening. It had been abandoned in front of a residence on Highland Street in Roxbury. The riot gun was found on the floor of the car. The doors and steering wheel were locked. The only fingerprints that were good were those belonging to a child. Detectives speculated that the thieves were professionals who had worn gloves.

Nina:

This one reminds me a bit of Billie Aggie. There was a degree of professionalism to it and it looks like it has a lot of parts in common with the other jobs we’ve mentioned. No violence, no real clues for the cops to follow. But something went wrong this time.

The following day, two warrants were issued in Brockton City Court against Vincent Geagan, aged 36. Yes, the same Vincent Geagan from the Brinks Heist. One warrant charged Geagan of assault with intent to kill the guard on duty. The second warrant charged him with armed robbery of the clerk in charge of the office when it was robbed. The police went to arrest Geagan, but he spotted them waiting for him and fled in his wife’s car, leading them on an 80mph car chase through Dorchester, South Boston, Roxbury and the South End. Geagan eventually ditched the cops in the Back Bay.

Lara:

Meanwhile, police arrested another one of the Brink’s boys. Thomas “Sandy” Richardson of Quincy was held as a “suspicious person”. At the arraignment Sandy tried to argue that bail should be reduced because he was already out on bail for stealing rent money from a girl in Somerville. The judge rejected this argument, saying “all the more reason the bail should be heavy”. Can’t blame him for trying even if his excuse was completely fucked up.

Nina:

At least he tried!

Geagan and Sandy were also suspected of participating in the Diamond Shoe payroll robbery in March. Geagan had a long police record dating back to when he was just 8 years old for “malicious destruction of property.” He was placed in Shirley School on charges of armed robbery in 1924, and paroled in June 1926. In October 1933, Geagan was discovered in Medford doing a break-in. He’d entered the building through a broken window in the back of the building. He had license plates on him. Bail was set at $3500. The following month Geagan was arrested in New York City for violating his bail by leaving Massachusetts. Six months later he was sentenced to six months for a hit and run. Which he obviously didn’t serve because he was out and about getting into more trouble.

Lara:

On October 18, the police found Geagan’s car abandoned in the South End. It was registered to his wife. A brown coat found in the car was sent to the lab for any possible clues. As the days passed, and Geagan’s arrest seemed less and less likely, the police announced that they had discovered that Geagan had been taking flying lessons at the East Boston airport for several months prior to the Brockton City Hall holdup. They speculated that Geagan had boarded a plane and taken off for parts unknown. He would have been much better off if he had done that.

Nina:

As always, none of these theories make any sense. No wonder the cops never solve any crimes.

Lara:

Seriously! Why would you need flying lessons in order to board a plane flown by someone else? Talk about grasping at straws!

Nina:

Every time!

But instead Geagan was discovered in Winthrop on November 1, apparently by accident. A warrant had been issued to narcotics agents to search the house where he was staying. When they arrived, Geagan and a friend, James Barry, attempted to escape out of a second floor window, leaving the two women in the house behind. The authorities came up empty on the drugs, but seized a paper bag containing about $1700 stuffed in a sewing machine drawer. Geagan, Barry, and the two women professed ignorance of how the money came to be there, and not one of them would lay claim to it.

Lara:

Talk about picking the wrong place to go on the lam!

They were held on a technical charge of larceny “from persons unknown”. Geagan lied about his identity to the police in Winthrop, giving them the name Edward McLaughlin. I can't. Was he imitating Punchy?

He was sent to Boston to be fingerprinted and still managed to keep the con going. He almost got away with it, too. But the newly appointed police chief in Winthrop asked for help from Boston to make positive identification before bail was granted. Two cops from Boston sent to Winthrop identified Geagan as wanted in the Brockton City Hall robbery.

Nina:

Meanwhile, Winthrop police obtained a second warrant to search the house again. When they returned the women who had been with Geagan when he was arrested had disappeared. The house was searched from top to bottom this time. The police found a suitcase with clothing similar to the uniform worn by the thieves in the Brockton job. They also discovered two sets of 1934 license plates in the cellar, one from DC and the other from RI.

Brought back to Boston and arraigned the following day, Geagan pleaded not guilty, and requested the presence of his attorney, Julius Soble. Bail was set at $50,000. Soble told the judge that he felt such an amount would prejudice a jury, but the judge was unmoved.

Lara:

Geagan was placed in pre-trial detention and held until a Grand Jury could be put together in Plymouth County. In February the Grand Jury came back with the indictment. Bail was set at $40,000, despite Soble’s protests.

Jury selection began on February 19. Soble argued that residents of Brockton should be excluded from the jury due to potential bias. He won his argument, but the pool of potential jurors was exhausted and two plainclothes police officers had to be drafted to fill in the final spots.

If that’s not grounds for a mistrial, I’m not sure what is.

Nina:

Well, you aren’t the only one who shared that opinion. The following day, Soble got a mistrial declared based on the addition of the police to the jury. But he didn’t get much of a reprieve. A new jury was chosen, and the trial began the same day.

The prosecution rested its case on February 25, and Soble began his defense. Geagan took the stand and testified that he’d had an appointment at the dentist’s office the morning of the heist. Afterward he went to his mother’s house in Charlestown where he spent most of the day. He headed home to Dorchester at about 4pm, driving his wife’s car. As he drove up to his house he spotted a police officer talking to his neighbor. As he came nearer, Geagan heard someone say, “there he is now”. Still on probation and with a suspended license from the hit-and-run in May, Geagan fled.

Lara:

He abandoned the car near Northampton Street, and took the El to Charlestown. There he called his wife and arranged a meeting spot. After they parted, he took a train to Rowe’s Wharf and then to Winthrop, where he walked to Cecelia Berkowitz’s home at about 8pm.

Nina:

Cecelia Berkowitz was born Cecelia Saxe in Russia in June 1903. Her father, Max, immigrated in 1904 and the rest of the family arrived two years later. By the time of the 1930 census, Cecelia was living in Watertown on 65 Salisbury Rd with her husband, a butcher, and their two year old son. She was later arrested on charges of being an accessory after the fact in the Brockton City Hall holdup. In October 1935, she received a 5 year suspended sentence. James Barry was sentenced to two years in the house of corrections but was given a stay of execution pending appeal.

Lara:

Geagan admitted that he gave Cecelia a fake name, calling himself John McDougal from Staten Island. He never left her house, apparently knowing at this point that the police were still looking for him in connection to the robbery in Brockton. When the police eventually found him, Geagan stuck to his fictitious story and gave them the same false identity.

Geagan’s testimony did nothing to help his case and he was sentenced the following day to 28 to 38 years for the robbery and another seven to ten on the charge of assault with intent to kill. The court decreed that the sentences should run concurrently. He was placed in solitary confinement at Charlestown State Prison the following day. He tried to get a new trial in 1935, but was unsuccessful. However, he was paroled in 1943, and you know the rest of his story.

Let’s move onto Maybury!

Nina:

You just like saying that!

On October 16, 1936 three men robbed the payroll of the Maybury Shoe Company in Rochester, New Hampshire of $10,200. The paymaster exited his car with the money for the afternoon’s payroll. Another employee was there to meet him, but both men were held up between the car and the factory. Three men emerged from a parked car with its motor still running, snatched the bag of money from the paymaster and quickly made their escape. Neither man had a chance to react. The event happened so quickly that it was unclear if there were three or four thieves total. All roads lead to Maine, so, of course, the car had Maine registration plates. The factory was close to the Maine border, so this wasn’t exactly surprising.

Lara:

I want to make some bad Andy Griffith joke about the whole Maybury thing, but I’ll spare our listeners. And spare myself from coming across like an old broad! Our younger listeners won’t have a clue!

The following Monday the police from Boston sent photos of Tommy Callahan to the local authorities. A witness claimed to have seen him loitering in the vicinity of the factory for several days prior to the robbery. Tommy was on the lam having escaped Charles Street Jail earlier in the year.

Nina:

We need to tell that story at some point because it’s really funny.

Meanwhile a young woman had been arrested as an accessory to the crime. Catherine MacKinnon had blocked the police from pursuing the robbers by deliberately stalling her green coupe in two different locations. City employees had to come and pull her car out of a ditch before the authorities could continue on their way. Of course, the robbers had gotten safely away by then.

But when the police checked the registration on Catherine’s vehicle, they discovered that it was not registered to her but to a man believed to be a friend of Tommy Callahan’s, John A Bolton, AKA James A Barry. The same James Barry who had been arrested with Vincent Geagan in the narcotics raid in Winthrop back in 1934.

Lara:

In the vehicle’s trunk the police found: three felt hats, two checkered top coats, a large zipper bag, a blanket and two pillows. Catherine denied knowledge of any of the items or the events surrounding her arrest. Unable to pay the bail of $15,000, Catherine was held on charges of being both a principal and accessory after the fact.

Nina:

The trial began on February 23, 1937. Pretty and auburn haired Catherine pleaded innocent to the charges. Jury selection was completed in 90 minutes and the jurors were transported to the scene of the crime after lunch.

While Catherine’s attorney and the judge were waiting for the jury to arrive at the scene of the crime, the defense attorney’s car crashed into the judge’s car. The judge was uninjured and seemed more amused than upset by the incident.

Lara:

Really, you can’t make this shit up!

The return to court that afternoon brought more revelations. The Henry MacKinnon named in the charges turned out to be Henry Baker, who you’ll also probably recall from the Brink’s case in 1950. The authorities alleged that Baker was a member of the Gustin Gang. Henry had a record dating back to 1924 when he’d been arrested for breaking and entering, and sentenced to 5 years.

Catherine told the court that she had met Henry in a nightclub. Baker had taken her to an apartment that he claimed belonged to a friend who she never met. Henry told her he was a drug salesman, and Catherine claimed to never suspect otherwise. She did admit to hiring an apartment for him in Quincy and placing the bills in her name, including a telephone line.

There’s no shortage of suckers!

Nina:

Then the payroll guard, Wightman, was put on the stand. Catherine’s attorney reduced the man to near tears when he got Wightman to confess that he’d had an ongoing relationship with Catherine’s sister for about five years and had been paying for her apartment in Boston for the previous 18 months. Wightman wasn’t the regular guard, but had been substituted at the last minute because he was free at the time of the payroll delivery.

The couple had had a fight the night before the robbery, and Wightman had threatened to leave the country and take work in Canada. This was apparently not the first time he’d made such a threat. Catherine’s attorney also elicited from Wightman that he was estranged from his wife and was in court for non-payment. The goal with this line of questioning was to make it appear that Catherine had a good reason for being in Maybury at the time of the robbery: the reconciliation of her sister and her sister’s boyfriend.

Lara:

What a fucking soap opera!

The jury deliberated for four and a half hours before finding Catherine MacKinnon guilty on March 1, 1937. She was sentenced to three to five years in state prison. Neither Henry Baker nor James Barry had been found by then.

Nina:

Exactly one month later, an anonymous phone call led the Cambridge police to a parked car on the corner of Massachusetts Ave and Linden Street. Inside the car was Henry Baker. At first Baker gave his name as Henry Banning, and a fake address in Worcester. But fingerprints soon proved his real identity. Henry had been arrested in Brookline in September 1935, and charged with breaking and entering the apartment of Brown University’s baseball coach. He made the $15,000 bail, and had been on the lam ever since. Baker was described as having a large scar on his chin and several front teeth missing. This description matched that of one of the robbers in the Marbury payroll robbery.

Lara:

Henry told the police that he had been staying at the YMCA in Cambridge. There the police found a typewriter with the beginning of a letter reading “Dear Catherine...”

Nina:

He was writing to her in prison! True love!

Lara:

Told you it was a soap opera! Bet he didn’t send her any canteen money.

Nina:

He couldn’t! All he had were the slugs he was using in the phone booths!

Lara:

Cheap bastard!

Ten days later, Henry Baker was sentenced to 4-6 years for defaulting on his $15,000 bail. Catherine served her time in the State Prison in New Hampshire as a housekeeper for the prison warden and his wife.

Nina:

In 1944, Henry was arrested in Los Angeles for dodging the draft. He and Catherine married in 1952. Henry passed away from pneumonia in 1961 while serving his sentence at Walpole for the Brink’s job. Catherine Sybil MacKinnon Baker passed away in 1994.

To put a nice bow on the end of the story: Wightman and Catherine’s sister eventually married too.

Lara:

I’m glad this saga is over!

Nina:

After hearing the early stories of Baker and Geagan, do you honestly believe they planned and pulled off the Brink’s heist?

Lara:

I certainly have my doubts!

We hope you join us again next week when we will be covering the planning of the Plymouth Mail Robbery!

As always, thank you for listening. Please follow us, leave a review and share an episode with a friend.

Lara and Nina:

BYE!!!!